Out onto the ice

It took an enormous amount of effort, but on Thursday we ventured out onto the sea ice with our train of sleds and snow machines. The tucker is our strongest (and slowest) vehicle, and it is pulling both our yellow research sled and a pair of snowmobiles. The red Pisten-Bully is pulling a second sled with several drums of diesel, a generator and assorted science gear. The weather was clear, cold and windy, with snow in the long-term forecast.

Initially we followed the Cape Evans sea ice traverse out of town: this route is a flagged and reconnoitered sea ice 'highway', so we were able to travel at maximum speed without having to stop and check the thickness of the ice. (Note that 'humming along' in Sno-cat is going about 3 mph). After two and a half hours on the sea-ice highway, we turned off the traverse and cut fresh tracks across the snow towards Inaccessible Island. The island is a big hunk of basalt rising straight out of the Ross Sea, and as we rounded the tip of the island, we saw a line of Weddell seals stretching off into the distance, evidence of large cracks in the ice. We tested a number of possible routes through the area, but all of the cracks were too wide and thin to safely cross.

We followed our tracks back to the sea ice road and continued north, passing around the other side of Inaccessible and trying our luck north of some large grounded icebergs. Here there were fewerbseals, and sea ice was more uniform, but we still ran into several large cracks, and by the time we had surveyed our route, it was past nine in the evening, and we needed to consider setting up camp. The wind had picked up noticeably, so we decided to head back towards Cape Evans and get some shelter from the coming storm. We were located near the hut that Robert Scott built for his 1911 Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole, but spending the night in the area is discouraged, as the area is a world heratige site. McMurdo Operations alerted us to a warming hut located behind Cape Evans, sheltered from the continental wall by a glacier on one side and a large basalt wall on the other.

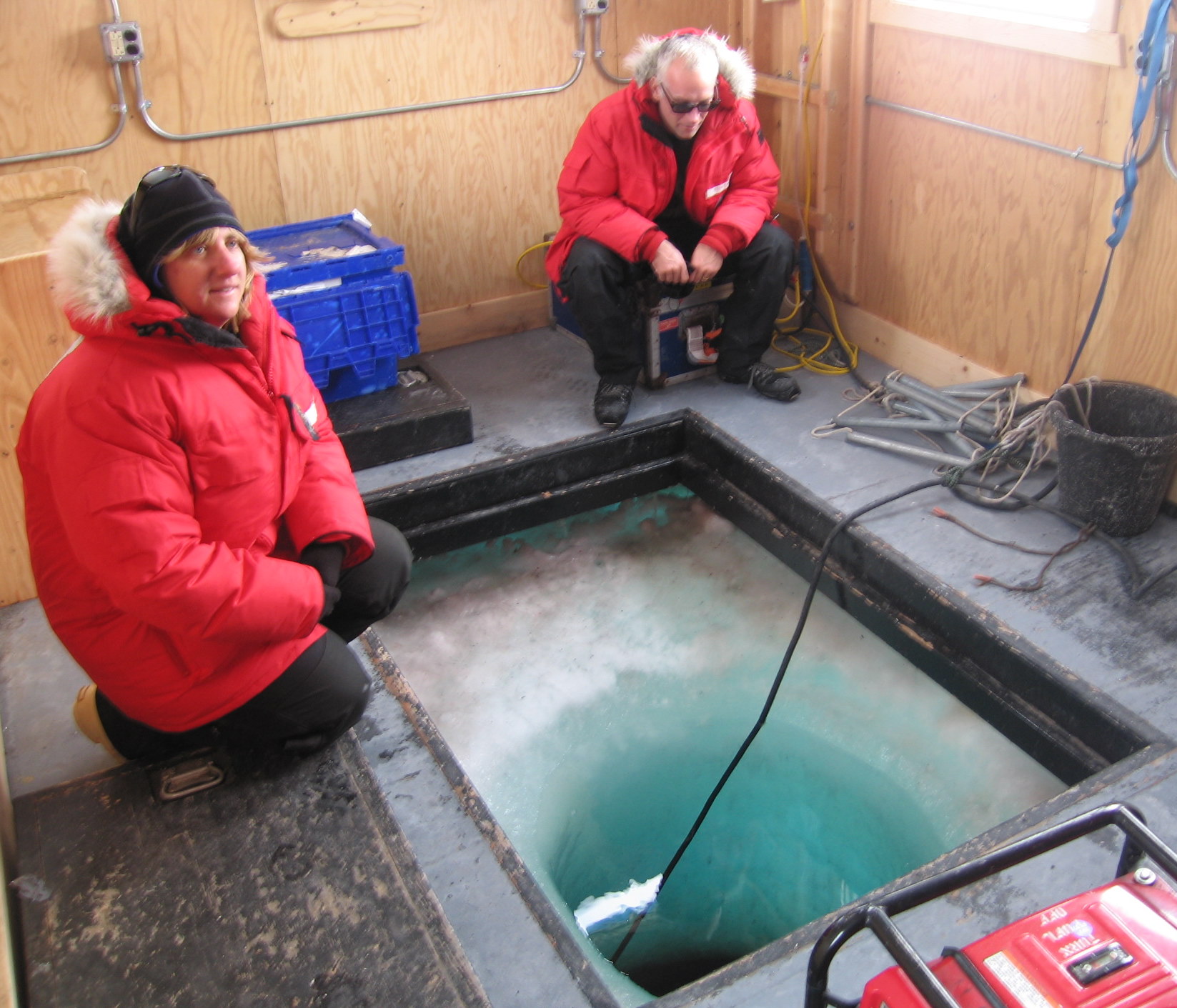

The hut turned out to be a dive shack kept heated to prevent the dive hole from freezing over. This presented some hazards when walking around the hut - one of the first casualties was my camera, which tipped out of my pocket and is now somewhere on the bottom of the Ross Sea. Still though, it was far better than being camped out on the unprotected sea-ice and blasted by wind, so we brought in folding chairs, sleeping bags and a portable kitchen, prepared to hunker down while the storm passed.

And what a storm! I grew up in rural New Hampshire and lived in Siberia, so I've experienced my share of foul weather, but there is nothing like a Condition 1 Antarctic storm to give you new respect for the raw power of nature. The visibility progressively dropped and the sky darkened, and the snow began to fall. It became impossible to tell whether the snow was actually falling or just blowing off the glacier, and the hut shook in the gusts. We had good radio communications with McMurdo Station, so we were never in danger, but we were certainly not going anywhere anytime soon - Hut 12 was our new home.